Hey Team Animalogic! Jess Keating here. I’ve been co-hosting Animalogic: Second Nature for a little while now, and it seemed high time to properly introduce myself. And what better way than to share something near and dear to my heart?

As a zoologist, author, and illustrator, I’m always happy to learn about remarkable women of history in fields of all kinds, particularly those whose names have been otherwise overlooked for their contributions. I’ve written a handful of books about incredible women who have changed the world, but there are always more to discover. I hope they’ll inspire you today to take a risk, learn something new, and maybe even share their stories with someone else who needs them.

Without any adieu whatsoever, here are five women who rocked the world of science that you ought to know about. Presented, of course, in random order. Buckle up!

Ada Lovelace

Starting off with one of the classics, our girl Ada Lovelace is thought to have written instructions for the first computer program. And get this: it was way back in the mid-1800s. She was the daughter of the famous poets, Lord Byron, and showed an aptitude for math at a young age. At seventeen years old, she met a dude named Charles Babbage, who happens to be known as the ‘father of the computer’ for his invention of the ‘difference engine, which calculated numbers.

With him acting as a mentor of sorts, she started studying mathematics at the University of London. Fast forward though a lot of hard work, calculations and what I imagine to be a massive amount of late night scribbling in her notebook, Ada concocted a way for codes to handle both letters and symbols, along with numbers, in Babbage’s machine. Her work was published in 1843, but her full name wasn’t used: instead she signed her work “A.A.L.” Over 100 years later, the U.S Department of Defense named its newly developed computer language, “Ada”, in her honor.

Eugenie Clark

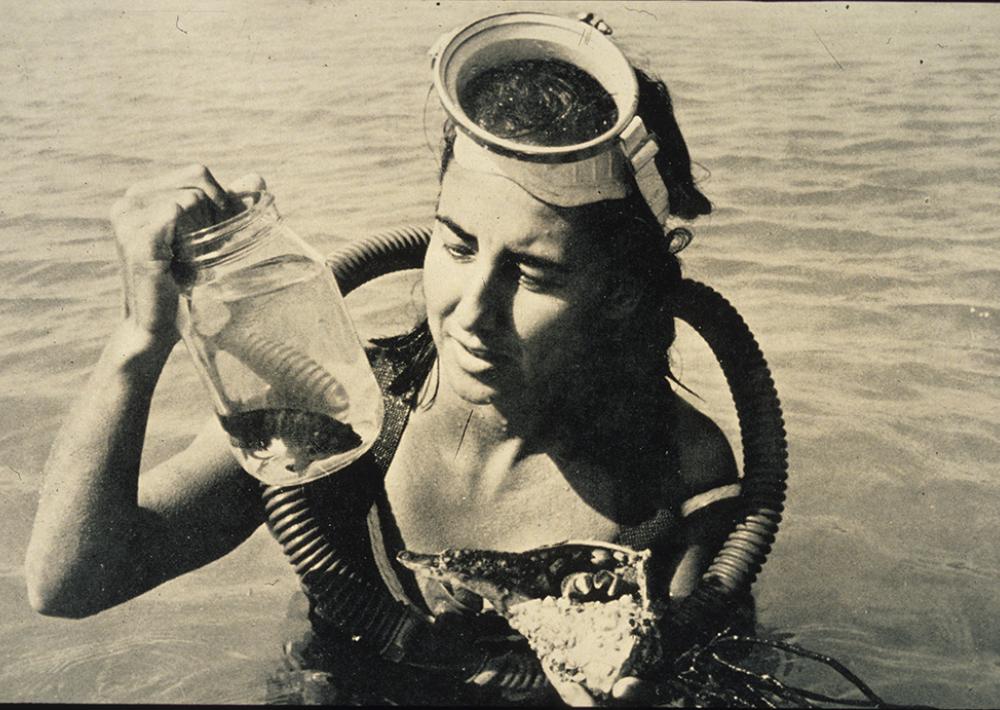

Full disclosure: I am biased as all heck about this woman, and I adore her and her work so much that I wrote a book about her. Eugenie first fell in love with sharks and fish when she visited the aquarium at Battery Park in New York City as a child. She was encouraged to become a secretary, or a housewife, or even to take up typing, so she could work for a scientist one day. Well, this didn’t sit well with Eugenie, and she decided instead to become the scientist herself.

She made a ridiculous number of discoveries throughout her inspirational and daring life, but she’s perhaps most well known for her work with lemon sharks. At the time, it was thought that sharks were mindless killers, both stupid and mean. But Eugenie’s work showcased another side of these animals: she trained sharks, very much in the same way that one would train a dog. She even learned that sharks could remember their training for months afterward. Both Eugenie and her sharks were underestimated, and she managed to prove people wrong on both counts.

Yvonne Brill

Yvonne Brill is perhaps not a name you’re familiar with, but let’s remedy that right now, because she is partly responsible for…nearly every global communication of your life. Much of our communication these days is possible because of communication satellites, locked up far, far away in orbit surrounding our planet. Yvonne Brill is the reason these satellites don’t fall out of orbit. She was, quite literally, a rocket scientist.

Yvonne Brill is perhaps not a name you’re familiar with, but let’s remedy that right now, because she is partly responsible for…nearly every global communication of your life. Much of our communication these days is possible because of communication satellites, locked up far, far away in orbit surrounding our planet. Yvonne Brill is the reason these satellites don’t fall out of orbit. She was, quite literally, a rocket scientist.

Yvonne Brill is perhaps not a name you’re familiar with, but let’s remedy that right now, because she is partly responsible for…nearly every global communication of your life. Much of our communication these days is possible because of communication satellites, locked up far, far away in orbit surrounding our planet. Yvonne Brill is the reason these satellites don’t fall out of orbit. She was, quite literally, a rocket scientist.

Developing a rocket is never an easy job, but Yvonne took things once step further and devised a new rocket engine called a “hydrazine resistojet” (which sounds like it’s right out of the Jetsons, right?) This is a fancy way of getting your spacecraft to propel through space by heating a non-reactive fluid. It was first used on a spacecraft in 1983, and has since become the industry standard as far as space satellite science goes. Oh, and she also contributed her brilliance to a series of rockets for Nova’s moon missions, the Mars Observer, and the first weather satellite. And bonus point: she’s Canadian!

Ruth Patrick

Here’s a pick for the nature lovers out there. Ruth Patrick was born in 1907, and her father was a hobbyist scientist with a particular love of botany. It was no surprise when Ruth showed an aptitude for plants at a young age, and ultimately became a botanist and limnologist. (A limnologist is someone who studies inland aquatic environments!) Not only did she author 200+ scientific papers, but she also used her knowledge to establish research facilities and devise ways to measure the health of our freshwater ecosystems.

Ruth’s research explored diatoms—she loved the invisible worlds found in water—and even volunteered to work without pay for eight years, as a curator of microscopy for the Academy of Natural Sciences. A passionate advocate for clean water, she even developed the diatometer, a device which allows us to better study diversity in water ecology. Both Presidents Regan and Johnson sought her advice to tackle water pollution and acid rain, and she worked tirelessly to help develop guidelines for the US Congress Clean Water Act.

Leone Norwood Farell

Another Canuck for the list, Leone was a literal lifesaver. Born in 1904, she was one of the few women at the time to obtain a PhD at the University of Toronto. Her speciality was the study of fungi. She also studied all kinds of toxoids, as well as antibiotics, penicillin, and vaccines to prevent diphtheria, cholera, and whooping cough. A crucial moment came at the invention of a “rocking” method, which gently rocked large bottles contain pertussis bacteria, which stimulated its growth for the production of a vaccine.

Years later, in 1955, the Salk trials were announced. This was the largest medical experiment known, involving almost two million children in Canada, Finland, and the US. Working to create a vaccine for polio, Leone’s rocking method (known as “the Toronto Method”) was responsible for the creation of about 3000 litres of poliovirus fluids. The successful mass production of such a vaccine had world-changing effects, and despite her incredible contributions, Leone went back to relative obscurity after she helped saved the world. Luckily, you’re learning about her today, so that’s one wrong set right.

Despite their differences in specialities and how they approached their work, all of the women on this roundup share two thing in common: brilliance and grit. They pushed boundaries, set their sights high, and managed to do their thing in their own way, despite doubts, ridicule, and even harassment in their fields. We all leave a mark on the world, but these women left more than that: they left the world better than they found it. And no matter who you are, or where you come from, I think we can all agree that’s pretty freaking great.