For over thirty years now researchers have been trying to explain changes in the Australian archaeological records from around 5,000-years-ago, when people suddenly began using new tools, eating harder to process foods, and hunting a wider array of animals. While many would like to think these developments were the result of increasing human ingenuity, people like Jane Balme, an archaeologist with the University of Western Australia, have considered another possibility right from the start.

Balme thinks ancient Aboriginals got a big leg up, or paw up as it were, from bonding with another species that hit the shores of Australia around the same time: dingoes.

‘I immediately wondered whether this diversity was the result of dingo prey becoming mixed with people’s, [then] about the possibility that the prey may well result from dingo hunting but accompanied by people,’ says Balme. Aside from some chats with students, she didn’t do much with the idea. That was until people became more interested in how dingoes have altered the landscape, and just how much Aboriginal advancement was dingo-derived.

Balme got in touch with a fellow archaeologist, Sue O’Connor from the Australian National University, who lives in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, a place where people still use the dogs to hunt. After a deep-dive through the literature available on the relationship between humans and the dogs, the pair has uncovered a lot of evidence that dingoes and humans go way back.

Photo by Alexius Sutandio / Shutterstock

They concluded that the first dingoes arrived on the watercrafts of South East Asian immigrants, so were likely already friendly with humans. Once on land a few dogs escaped and became feral, but others stuck around camp. Humans continued to acquire more dingoes by taking pups from their dens, but the species was not domesticated—undergoing genetic changes to suit the union—just tamed.

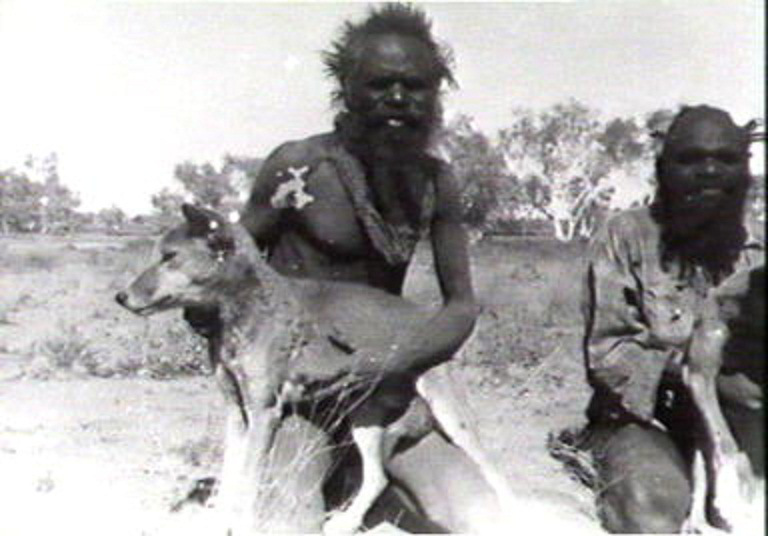

They also found that both men and women used the dogs. Previously it was thought dingoes weren’t horribly useful for hunting because they scared away large game. While this may have discouraged men, ‘dogs almost always accompanied women on their foraging expeditions and were often used to hunt small animals, such as goanna,’ says Balme. And female-dingo bonds were very close; women sometimes lavished puppies with care.

The pair cites the presence of dingoes in Dreaming stories, ceremonies, songs and rock art in some parts of the continent as evidence of their importance to Aboriginal life. The dogs were also a source of protection against outsiders and evil spirits, served as cuddle-worthy living blankets in the brutal Australian outback, beloved pets, and lended emotional support. Particularly good or beloved dogs were even given special burials.

Blame says this is just the start of their work. ‘We really know very little about the subject,’ she says, like the precise date of dingo fossils

While we may have a lot to learn, one thing’s for sure—dingoes and humans have an ancient bond—which may help explain why it took Lindy Chamberlain 32 years to prove that a dingo did in fact take her baby. People simply didn’t buy the good-natured wild dog would harm a human unprovoked.