Scientists have used the often slighted spider to prove that pesticides may have a much wider range of effects than first supposed.

Since Rachel Carson’s 1962 classic Silent Spring, it’s become common knowledge that pesticides and wildlife don’t mix, but precisely how these toxic chemicals alter animals on an individual basis is a complexity far less understood, much less studied. That’s because it’s only been a decade or so since researchers really began trying to figure out whether animals have quantifiable personalities. In other words, do certain individuals have predictable responses?

For the most part, it seems the answer is yes. However most pesticide studies still don’t factor in individual changes, something behavioural ecologist Raphaël Royauté is attempting to rectify.

‘Drugs and alcohol affect humans differently, so why not animals?’ he says. ‘By only looking for population level impacts, we might be missing the leadup to the larger event—and the warning signs.’

Recently Royauté, a former PhD student at McGill University, published a study in Functional Ecology, where he exposed jumping spiders to a general-use apple orchard insecticide.

Why spiders? As it turns out, the eight-legged arthropods are surprisingly personable. Some are more aggressive than others, or more curious. They also display different hunting preferences. Royauté says spiders don’t come by these traits haphazardly, so it’s important to determine whether things like pesticides change these patterns.

‘Each trait an animal acquires is the result of amazing selective pressures,’ says Royauté. ‘Altering them may also change an animal’s inherent defences or skills, and in turn, its chances of survival.’

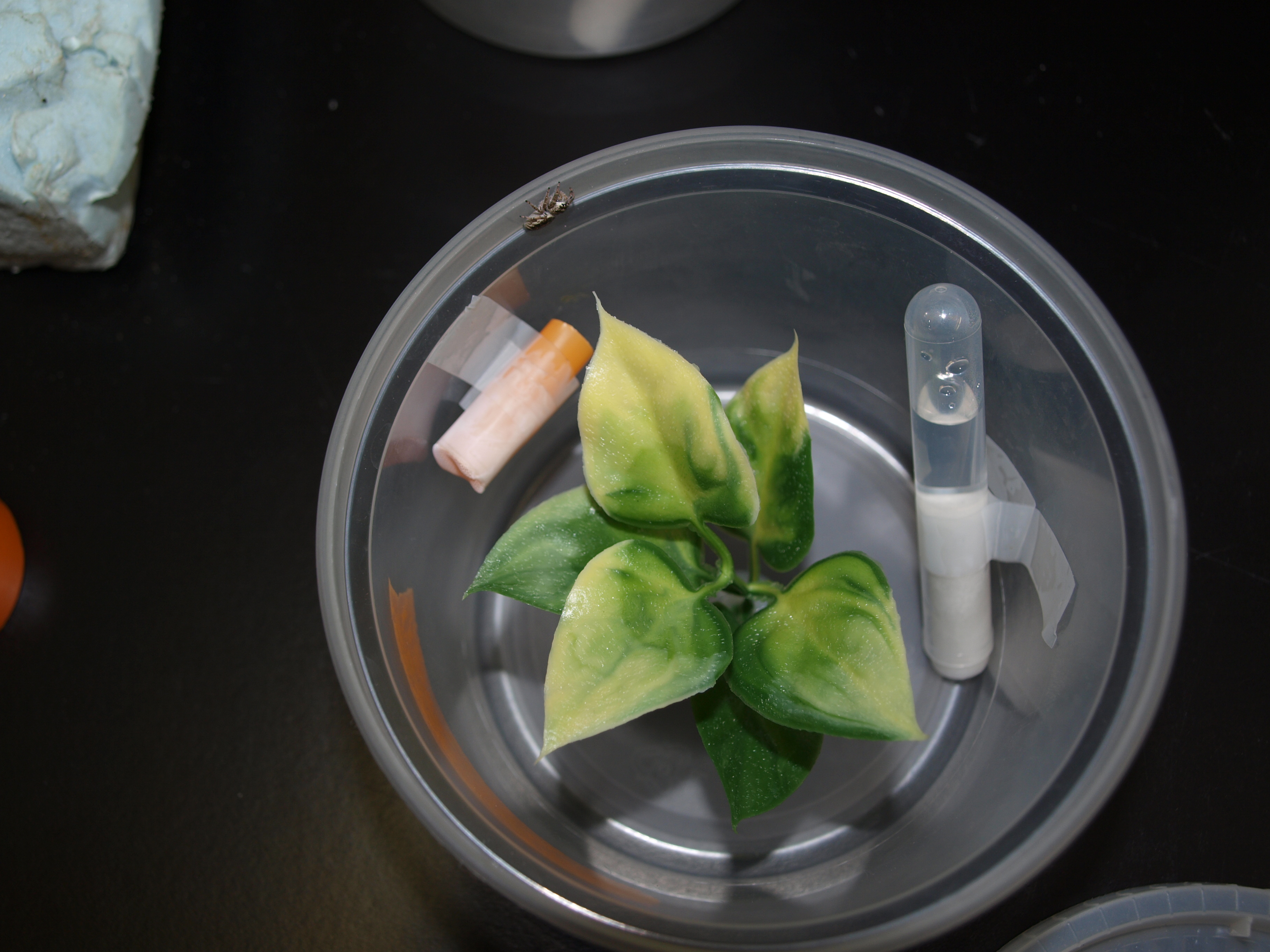

Royauté and his team collected wild parent spiders, then raised their own generation in the lab, making sure they got plenty of attention; each tiny jumper getting their own plastic straw to hide out in, and fake plants to do natural spider-things from, like watch flies.

The team determined each spider’s normal response to a few situations, like how much of the new habitat each would explore, and how they handled capturing fruit flies. Over time, some spiders were dosed with the pesticide residue by running over a chemical-covered hot dog warmer, ensuring an even, realistically applied coat. After being sufficiently doped up, all spiders repeated the same tasks as before.

While on the whole, the community didn’t change, certain spiders did, and there were notable differences between sexes. Some females showed impaired hunting abilities, some lunging at prey too rashly. Whereas some males covered less ground in exploration trials, running in circles instead of branching out.

Royauté says a lot more evidence is needed before policies or toxicity testing methods are changed, but his findings so far are certainly fascinating, and worth pursuing further. He says there’s something to be learned from the segment of his spiders that showed personality changes before others.

‘Imagine if these smaller changes turn out to have cascading effects. If spiders stop acting like themselves, this would disrupt the ecosystems they help regulate,’ says Royauté. ‘Surely if we found this kind of link in humans, we’d rethink how we determine [what level of exposure] is really reasonably fair, or safe, before subjecting ourselves to it’.