‘With the bicentenary of the death of the British explorer Mungo Park approaching, I thought it would be a fitting tribute to his memory to recreate his travels in post-colonial West Africa. I intend to follow the brief set for him by the African Association in 1795 to discover the River Niger and to follow its course to its termination, which was at the time unknown.’

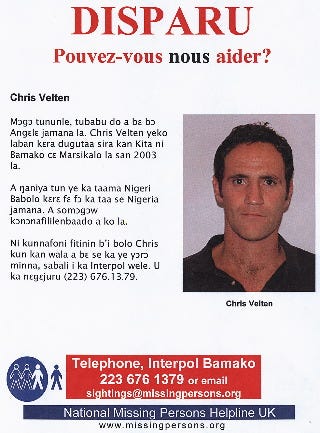

These words, typed by Chris Velten, would ultimately lead to his disappearance. Gone without trace — April 2003, somewhere outside the Malian capital of Bamako. But not quite. Over 13 years later, a number of individuals are today coming forward claiming to have seen the would-be 40-year-old alive and well and in Kenya, some 6900km and seven countries away from his vanishing point. But if such sightings are true, how did this bright and charismatic former zoology graduate come to find himself on the other side of the African continent?

More importantly, what happened to him in the hot, wild climes of Mali that led to the bright-eyed 27-year-old remaining far-distant from his family and friends to this day? In an investigation for Love Nature, Jamie Maddison examines the life and ambitions of Chris, and also of his sister Hannah, who continues the search for her brother in Nairobi — her world inextricably linked to that of her sibling, the lost explorer.

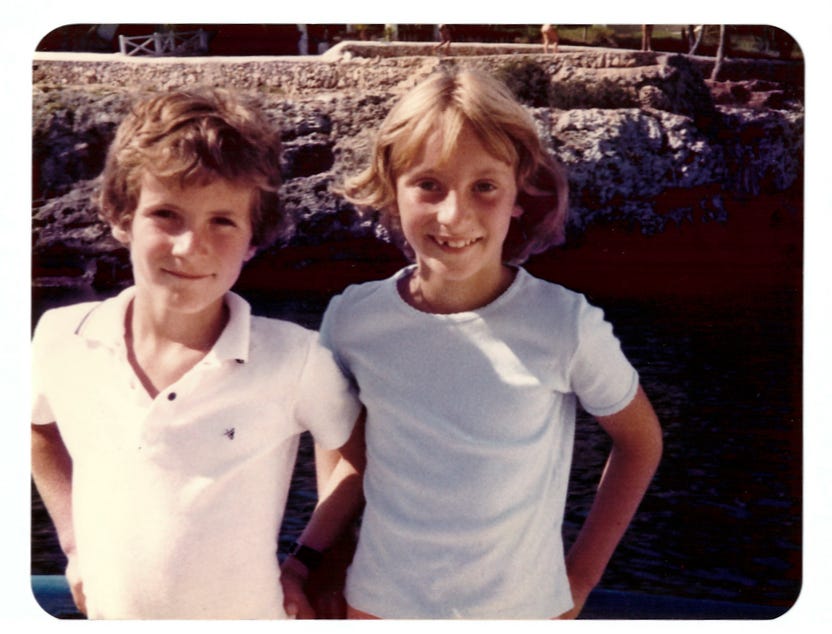

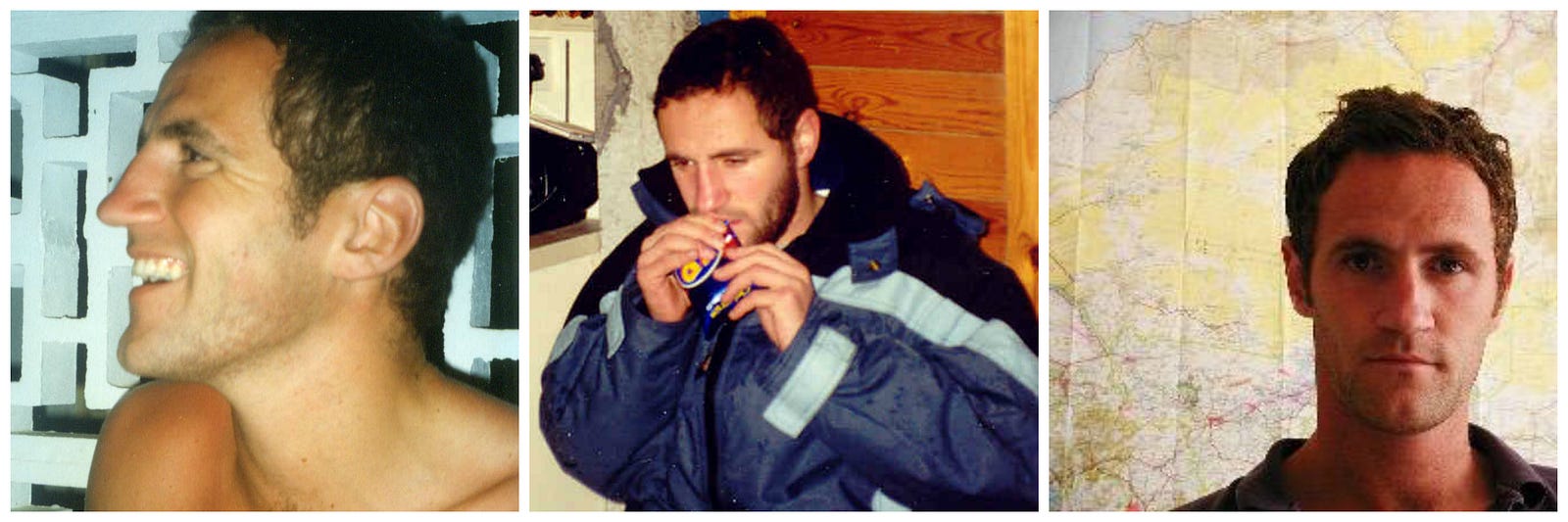

Christian Carl Velten was born on 7 July, 1975, the second child of Tim and Pauline Velten, following 14 months behind the arrival of his big sister Hannah. Ensconced in the idyllic countryside setting of East Sussex, just outside Wadhurst, the two children grew up experiencing the unhurried rural joys of life on the family farm; forever playing, making assault courses or jumps for their bikes in the farmyard or generally causing havoc around the house—as country kids do. ‘We farmed in conjunction with my uncle, so we had cousins close by,’ Hannah tells me over coffee and a plate of biscuits at her quaint village home just outside of Uckfield, also in East Sussex—drawings by her own children proudly pinned up around the place. ‘But apart from that, we were fairly cut off…Christian and I bonded really closely because we were playmates and brother and sister. We looked very similar too—people used to think we were twins. We just used to spend so much time together.’

Yet as is the case with many childhoods, time flies by far too fast and after primary school Hannah and Chris’ day-to-day lives began to diverge drastically. At seven, Chris was admitted to Holmewood House School, first as a weekly boarder then full-boarder. Then, aged 11, he started as a full-time boarder at Charterhouse, an exclusive educational establishment founded in 1611, attended by many English elites, including Robert Jenkinson, governing Prime Minister from 1812–1827. ‘I didn’t see very much of Christian after that,’ Hannah continues. ‘He would come home and there was a bit of a different smell to him, there would be a different haircut, there would be a different, you know…he wasn’t really my little brother anymore. It was all a bit weird.’

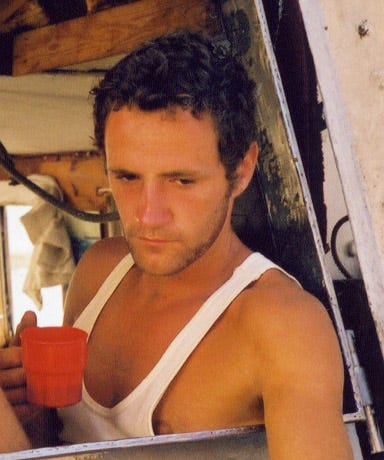

Hannah went her way, Chris went his, studying zoology at Edinburgh and joining the university boxing team. Tales of Chris is a blog set up so that his friends and acquaintances can write their recollections of the man who would later abruptly disappear from their lives. Through their posts, you can clearly discern an intimate sense of Chris’ ‘top-bloke’ demeanour—his endless goodwill, robust sense of humour, not to mention a determined adventurous streak. ‘He was very good with people; he had a charisma,’ recalls his mother Pauline, former model, now a dressage judge and keen gardener. ‘When he walked into a room everyone cheered up because he was always funny, always making people laugh. He was a great character. I say he was, he is, a great character.’

These warming sentiments are echoed by many of Chris’ former friends, such as Edinburgh student Charlie Coghlan: ‘After a few drinks Chris decided to spice things up and said that for a dare he would drink a bottle of chilli sauce. We poured the chilli sauce into a wine glass and Chris downed it in one. He then drank loads of beer and wine to put out the flames and as a consequence was shit-faced by the time we stumbled back to our flat.’

But there was much more to Chris than just jokes and japes. ‘I watched him go toe-to-toe with a guy who went on that year to win the British Universities Boxing Championship for his weight,’ his old university roommate Nick Blackford explains. ‘The battle only stopped when Chris twisted his ankle. We all knew something special was going on as the rest of us in the boxing gym stopped what we were doing to watch, something which had never happened before or since. He inspired me to carry on boxing after Uni, and I went on to box on and off for 15 years.’

Hannah saw many sides to her brother’s character. ‘On the other hand…’ she says, her voice slowing, as if she’s weighing up the significance of each word before committing to it. ‘Chris could be quite bolshy. He was very…I wouldn’t say fixated, but he could get quite arsey with people sometimes if he thought he was in the right. He was quite direct with people, happy in his own company and — particularly when he was travelling — he liked to be in control of what was going on. He could be quite a loner sometimes.’

Every long academic break Chris would go off travelling, one time on a trip around Europe with two friends he ended up being marched to a Bosnian police station at gunpoint during the height of the country’s 1992–1995 armed conflict; he’d gotten on the wrong train by mistake. Another time, he spent a year in Australia, working on a 1000-acre estate as a horse trekking guide and rancher, undertaking a two-week cattle-drive through the Blue Mountains. Later, he went deep into the outback to tend to a rancher’s thoroughbreds and get them fit for the Brisbane Races. On the way to that escapade, a freak outback rainstorm broke and deluged the area the bus was travelling though. His vehicle sank in the mud and it took a week before Chris was picked up by rescuers.

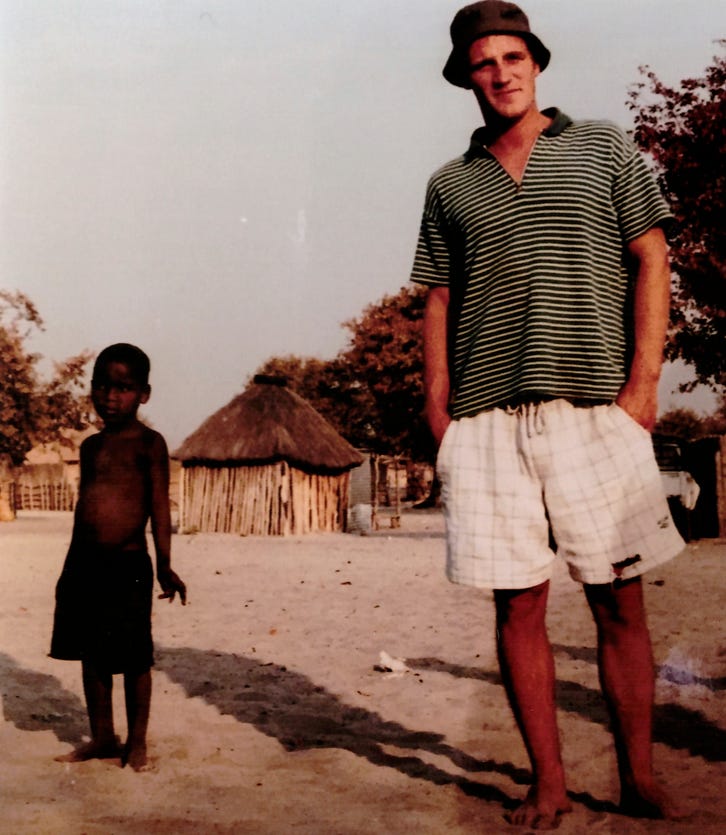

His wanderlust only grew stronger after university, the zoology graduate spending the summer of 1996 travelling in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia with friends. Two years later he spent 18 months exploring 27 islands in the West Indies, researching a comprehensive book about the wildlife of the Caribbean for a commission for Penguin Books. After his return he supported himself by pulling pints in a bar in Brighton, but the deal fell through — Penguin said the text was too academic, they’d wanted something simpler that tourists could digest and carry around — leaving two years of work without any outlet or any tangible benefits. The loss was a blow for Chris, by then 27, who redoubled his efforts to make a name for himself.

‘I think [after the Caribbean] he was at the stage where he felt he needed to do something,’ said Hannah. ‘A big project. Something dramatic.’

‘Bloody Bamako. I’m sick of hearing about bloody Bamako,’ Pauline used to say about her son’s chatter concerning the route of the little-known British explorer Mungo Park. Now living in Cornwall, Hannah initially learned that Chris was planning an expedition to Africa via the weekly phone-call she held with Mum, who seemed totally against the trip. And she had good reason to be. In 1795 Park set off into what was then the unknown, to extend the boundaries of African exploration. The Scotsman undertook a perilous mission — facing bandits from the notorious Tuareg and Fulani tribes, and also becoming imprisoned for four months by the Moors. Park’s second expedition, in 1805, was more tragic; he drowned in rapids at Boussa, in Nigeria, aged just 34.

‘What makes his achievements the more incredible is that unlike these later explorers, on his first journey Park undertook his travels alone,’ wrote Chris in a proposal document he put together for the production company he would be filming the adventure for. ‘I found the idea of undertaking such a challenging journey irresistible. I find him a truly inspirational character and I am fascinated by his motives for undertaking such an ambitious and perilous mission into the great unknown when no other European had previously succeeded in such a venture.’

There’s no doubt that Chris’ expedition was an audacious undertaking. The six-month-long journey would take him through some of the wildest parts of Senegal, Mali, Niger and Nigeria, covering over 2000 miles entirely on foot and — for the river sections — dugout canoe. Just before he left, Hannah came home (for the last six weeks prior to the trip Chris moved back in with his parents to conserve funds) from Cornwall to say goodbye. She remembers being taken aback by just how much of a mess his bedroom had become: piles of books, papers, maps, dictionaries — all related to the journey — filling every nook and cranny of the room.

‘He’d planned every day out meticulously; there was nothing left to chance, really. Mum was still uncomfortable about it,’ Hannah adds, ‘But Chris was 27. What can you do? You can’t stop him going.’

An estimated quarter of a million Britons go missing each and every year, around 425 of them abroad. Of all these people, 91% will be found within 48 hours and 99% of all cases are concluded within one year. But it’s that one per cent left over that proves so divisive to societal interest. Some vanishings such as that of Lucie Blackman in 2000 or Madeleine McCann in 2007 generate large headlines and voluminous column inches. Others such as Ian Mogford (1996) and Angela Reynolds (2014) pass by with only the most perfunctory interest from the general public. Unfortunately, it’s the latter that’s truer of Chris’ vanishing. Not that anyone knew Chris was missing at first; before leaving on 7 February 2003, he’d warned family and friends they were unlikely to hear from him whilst he was out in the wilderness of West Africa.

Tim Velten had a cousin with a friend living Gambia, so Chris had gone to stay with them for a weekend before the trip proper commenced. That would be the last time any of the family saw him. The seasoned traveller carried no mobile phone for his journey — arguing that he wouldn’t be able to charge it — and no GPS. This being 2003, accessible internet connections were practically non-existent. He did carry an abundance of batteries however, for his video camera, which filled up his rucksack almost entirely. The production company he’d liaised with had also wanted him to take a sound man and cameraperson too, but Chris had refused. He wanted to go it alone.

Wherever he went—even in the depths of Africa—Chris inspired goodwill, and many of the children he met on his travels would send letters back to the Veltens’ home address. This was Chris’ way of establishing friendships and gaining access to local communities. Whenever he chanced upon a working phone Chris would always ring home. On March 23, he phoned from the frontier town of Kita, one of the regional capitals of the Kayes Region of Western Mali, already 650 miles into his journey. He was calling to wish both his mother and father a happy birthday, the days falling just two days apart.

He seemed in good spirits. Up until recently he’d been using a donkey — which he traded in for a handcart when the terrain got too harsh for the animal — and was due to arrive in Bamako within a fortnight. Chris planned on joining the Niger River shortly after that, travelling along it for the rest of the journey until his arrival on the Nigerian coast, at Brass Island. The last positive sighting came a week or two later, walking along the road toward Bamako, although other reports place Chris’ last known location at a café, also on the outskirts of Bamako.

The letters stopped arriving; there were no more phone calls. At first his family didn’t worry — they’d hadn’t been expecting Chris to call — but, after a couple of months, they realised he should’ve passed through another major settlement by now, either at Timbuktu, or further up at Mopti. The expedition was due to end on 6 July, but Chris did not catch his flight home, provisionally booked for 22 July. Concern at home slowly transformed to anxiety, then quickly to action. His parents contacted the Foreign Office for assistance in locating their missing son.

‘During all this time I was phoning the West Africa desk at the Foreign Office,’ explains Pauline during a lengthy late-evening phone conversation with me; she’d been out judging at a dressage competition and had only just got in. ‘The guy there kept saying: “Oh don’t worry Mrs Velten—if anything had happened we would have heard. It’s such a safe place, nothing ever happens in Mali”.’

For the family, the subsequent months would prove a time of immense confusion, fear and frustration. Media reports written from the September after Chris’ disappearance indicate a ‘nightmare of red tape and silence’ for the Veltens, who felt isolated from the procedure and apparatus routinely employed by the State when searching for at missing person on home soil. It seemed to them that there was no formal protocol in place for helping find a British citizen missing abroad. On 16 August, Chris’ mother rang Sussex police. The first thing they did was search the family’s home. ‘They said it was because most missing persons are found in their own houses. Can you believe it?’ Pauline adds, ‘I mean, how bloody ridiculous.’

Vicky Paterson shared a flat with Chris in the last year of university. She became an integral member of the Missing in West Africa | Christian Veltencampaign, helping set up its website. She also managed to get in contact with Violet Diallo, former vice consul general to Mali, whose driver, a man called Samake, would become the first on-the-ground search party for the missing explorer. Samake went to Kita, the last known location Chris could be pinpointed to. Working from there, the driver traced Chris’ route a further 120 miles east, to the outskirts of Bamako, but the trail went cold after that.

Tim and Pauline were by now frantic to find out what had happened to their son. They found an ex-Gurkha officer willing to help and—along with another former roommate of Chris’, Sam Rice-Edwards—an expedition team was formed and dispatched to pick up from Samake’s efforts. In Africa for seven weeks, the team travelled through the continent, right past Timbuktu to Gao, searching over 700 miles of terrain, making endless enquiries and often following false leads. At one point hopes were raised when a lone white man was sighted on the river, but it turned out to be a German doing his own Niger expedition. No one had seen Chris and the team were ultimately forced to come home empty handed.

A few months later, via a series of twisting convoluted connections involving a call-in to BBC Southern Counties Radio, Pauline and Tim were put in touch with a Malian village chieftain and witch doctor. ‘He said: “I think he could track your son,’ Pauline tells me. ‘“What have you got of his that I can use to track?” Well when Christian came back from the West Indies he’d grown his hair long, a bit like dreadlocks, but natural curl. When he finally chopped it off, I kept some. So I sent it off to this fellow.’ The chieftain left his village to track Chris’ movements, for two entire years. What’s extraordinary about this account — apart from the extreme length one Malian tracker was apparently prepared to go to find a complete stranger — is that Chris’ alleged trail seemed to head south, into Guinea, not east in the direction of Niger like it was supposed to.

The crucial bit of information, fed from the tracker back to the Veltens via an intermediary, placed Chris at a highway sleepover stop south of Bamako. Speaking to the owner of this basic roadside accommodation, the chieftain learned of how a lorryload of silver miners had stopped their with an Englishman among their group ‘who was not a prisoner but seemed to be under their control’. The foreigner gave the owner his blue rucksack, which he showed to the tracker. Chris’ rucksack was also blue. But the account was never verified by anyone else, and the driver Samake was unable to rediscover the rest-stop, nor its mysterious owner with an Englishman’s big blue rucksack. The trail went cold once again.

But there were other sightings. One time an Islamic relief lorry driver, who’d seen the photos distributed of Chris, reported seeing a possible match near Ghourma-Rharous, just past Timbuktu. According to the BBC news report: ‘[The driver] had noticed him up there for some months and he knows he goes into the nearest market town to buy tins of sardines and then acts strangely.’ At another point, a man visiting the UK from Mali, claimed to have seen Chris personally, but died of kidney failure before he could provide any specifics. During a press conference around the same time, Pauline Velten voiced the families’ hopes Chris was still to be found: ‘We’ve had no word to say anything has happened to Christian and we have to hang on to that.’

Cornwall is a long way from East Sussex—over 11 hours by train but a life away culturally. As the search for her brother entered its zenith, Hannah found herself far removed from the action down in the West Country, embroiled in her own life and burgeoning writing career. By virtue of distance she remained insulated from the nightmarish daily ups and downs Pauline and Tim experienced; the promising leads and dashed hopes, transmitted constantly by a new fax machine, which whirred away busily in a corner of the family home. ‘It’s difficult to sort of explain because…Mum and dad lived every second of it because they were there,’ she tells me. ‘Their house was the base where everyone coordinated.’

‘Then, of course, once the media leave—because there’s no new information we can give them—people tend to go: “Oh okay, all right, well, he’s obviously not coming back.” They all walk away. Whereas, when you’re the family, the situation stays with you all the time. You can’t walk it off.’

‘To be honest, for my sanity, I had to think Christian was dead,’ Hannah admits. ‘I actually made up a story that he’d been eaten by a hippo on the river because it was the easiest scenario to accept. No people involved. It was the easiest thing in my mind to sort of lay it to rest while I got on with everything.’

‘I thought long and hard about what I am going to say…I would hate to give you a false lead but I remember in 2005 seeing this face but very thin…in Ghana…and he was begging! He was at the traffic lights near my old home (in Ghana’s capital, Accra) I usually ignore the beggars but it was unusual to see a white beggar. I rolled my window down to ask what his problem was and he said he had been travelling from country to country looking for his family.

I asked where he was from and he said ‘France, I think’ [but] he spoke with a British accent. I asked why his family was in Africa and he said they weren’t; he was giving me very contradictory answers and looked very confused himself. He said he was begging to raise money for a ticket back home. What makes me 80% sure it’s your brother was what he said as he appealed for money: are you a Christian, missy? Can you help me please? My name is Christian…’

This comment was left on Searching For Chris Velten, a Facebook page set up by Hannah Velten two months ago, some 13 years after Chris went missing and 10 years since the original website set up to find him was taken down. The reasons why efforts to find Chris resumed after such a long time sit as much in the realm of belief as they do new evidence having come to light, and they’re tied strongly to Hannah’s sense of identity, tightly bound as it is to the fate of her missing brother. The original search parties had come back empty handed, no death certificate was ever issued for Chris and there’d never been a funeral. ‘And that’s the biggest thing about all of this is that you don’t have closure.’ Hannah says, tears welling up behind an intense and determined gaze. ‘We had hope, but we’d never had any closure on it.’

In July 2015, she arranged a 40th birthday party for the absent Chris, inviting all his friends and the extended family along, to celebrate the charming man still missing from all of their lives. It was a catalyst, for her mentally, but also a signal of changing winds. A few years earlier, Hannah had chanced upon some pictures of Chris whilst going over files on his old laptop. One of those was a picture of her brother from the West Indies. Drenched in sweat, he stares out at the camera, holding in his hands a six-foot-long snake. She liked the picture and published it in her business blog — a quiet corner of the internet where she could show off examples of her work as biographer (a career in no small part inspired by the need to tell Chris’ story); a site relatively few people would actually visit or read unless you were a client, a friend, or a blood relative.

Fast forward to this year. Feeling renewed hope, Hannah decides to believe Chris is alive; after all, the family had never received any conclusive evidence to suggest the contrary. She went on radio, and set up ‘Searching for Chris’ Twitter and Facebook pages. The push garnered her a surge of renewed press interest, which brought the new search to attention of Raabia Hawa, a Kenyan conservationist. Hannah explains what happened next: ‘She got in touch with a mutual friend,’ explains Hannah, ‘and said: “I know those pictures that you’ve posted, the one of the boy with the anaconda, I know that picture. About two years ago, this guy sent me a friend request on Facebook.”’

Unfortunately, not knowing the individual, Raabia deleted the request and all efforts to trace the account have since failed. The significance took a while to sink in. It was only after a few days that Hannah realised the picture could only realistically have been used by Chris, stalking his family remotely online, following her work, and finding a good picture of himself to use for social media, perhaps contacting the conservationist to get back towards his working with wildlife roots. Raabia is indeed a good contact to know if you were looking to set yourself up in that space.

‘Something obviously went majorly wrong for him and he did, at some point, lose his mind.’

The internet latched onto the Kenya connection. All of a sudden sightings were coming thick and fast from Nairobi: people had seen him as a homeless man in the slums, as a white preacher on a bus, as a john going into a hotel with his ‘girlfriend’. Hannah was initially sceptical, as she explains while we sit together watching another cafetière of coffee brew. ‘You know…’ she begins, before immediately correcting herself. ‘Well you don’t know, but when you lose somebody you get a lot of people that go “Oh, yeah. I’ve seen him.” It’s just human nature to be like that. But nobody could get me a picture, nobody could get me video. So without that kind of evidence, it’s a no-no.’

Still, the image of Chris alive and in Africa remained bright in her mind. Hannah felt drawn to it, especially after a telephone conversation with the women who’d seen Chris at the Accra traffic lights. ‘Somebody obviously found Christian in Mali, looked after him, pointed him in the right direction down to Ghana where he would be safe [a lot of Western NGOs and charities base themselves out of Accra]. She said he was sunburnt, filthy and looking really thin like he’d just got out of a hospital bed. Just knowing that’s your brother…’ Hannah trails off, ‘I can’t think about it too much because it’s too upsetting. But at that point, obviously, he was in that state.’

‘Which explains why he hadn’t been in touch,’ she continues. ‘Some people assumed that when Christian went missing that he wanted to disappear, that he’d used his trip as an elaborate way of getting ‘lost’ and not coming back—running away for whatever reason. We knew he’d never have done that, but this kind of sighting gives evidence that something obviously went majorly wrong for him and he did, at some point, lose his mind.’

Speaking with Pauline you sense the same story is held true across the entire family: Chris was attacked, robbed and hit on the head; he lost his memory and lost his mind. But this version of events is not without its difficulties—after all, why would a person who has been the victim of a dreadful attack not immediately present themselves at any embassy anywhere on the continent and ask for help? Even if Chris did lose his memory and his common sense as a result of a dreadful and life-changing attack somewhere outside Bamako, what is one to make of his seemingly skilful and passport-less push into Ghana, then potentially Kenya, nearly 7000km away?

The narrative stumbles again, both for Pauline and for Hannah, at the point where Chris regains his memory—which if you’re to believe in his alleged Facebook friend request to Raabia Hawa using Hannah’s blog picture—you must. For to accept that, the family have to also accept that Chris knows who he is, and thus is deliberately keeping himself from reconnecting with his old life. All this leaves the Veltens with a circle they cannot square.

‘I find it hard to believe that he’s in Kenya to be honest,’ Pauline admits. ‘I can’t believe he’s still in Africa. If he’s still around, why would he stay in Africa if that’s the place where he came unstuck? I know when he travelled he was always glad to get home. Hannah seems to think that Chris might think we wouldn’t want him back after such a long time but I can’t believe that. That would be out of character for him. I really don’t know. Your guess is as good as mine,’ she concedes at last, and just for a moment a sense of weariness slips into her measured and refined speech.

Hannah is more passionate, fired up with a burning belief in her brother’s wellbeing. Over the past month she has placed appeals for Chris to come forward in all of Kenya’s prominent newspapers, The Standard, The Star andThe Nation, at no small personal expense. Today, her phone is always on, placed up against the window where it gets the best reception—in case Chris rings one of the appeal’s two numbers that will connect him with the British High Commission in Nairobi, then onto Hannah. ‘It’s so personal now,’ she tells me as our interview reaches its conclusion, coffee all drunk and me with a train back to London soon to catch. ‘I worry that I’ve put too much into this. I’ve laid everything too bare. But then I think, if that’s what I have to do to get Christian back then…’ she tails off again. ‘I can’t believe he won’t come forward. I just have to…I have to…I don’t know.’

I ask her if she believes in fate. Hannah takes a moment to think about this, repeating the question out loud to herself, as if re-examining years of loss and pain from a new, perhaps cosmic perspective. ‘Yes.’ she says at last, ‘I believe Christian’s supposed to be found now. But, at at this point, I don’t know what the significance of it all is. I don’t know why we’ve had to live with all this for 13 years. If I think about it too much, I am fucking angry about it all. But obviously there’s a reason for it because I can’t believe that he would go through all of this for no reason.’

Before I go, Hannah shows me a book someone had sent her recently, since she restarted the search. The Fox and the Star tells the story of a friendship between a lonely fox and the star who guides him through the deep, dense and incredibly dark forest. But one night Star is not there, and the mourning Fox is forced to confront the cold blackness of the forest all alone, embarking on a journey to find his lost friend in a place beyond the world he knows. Along the way, Fox discovers a woodland filled with new friends, new adventures, and it’s only when the animal comes to terms with the loss of his former companion and learns to enjoy life again that the greatest gift he could ever wish for comes to him at last: a big, bright, and completely star-filled sky.

The search for Chris Velten continues. If you believe you have any information on his whereabouts, please contact Hannah using her Facebook page: Searching for Chris Velten.