We’ve heard of some weird sports in our time, from egg throwing and cheese rolling to bog snorkelling and outhouse racing. But in our minds, one of the weirdest (not to mention most unethical) sports that ever existed has got to be octopus wrestling.

The activity is obviously no longer in existence or socially acceptable, but not too many decades ago it was all the rage—to the point where world championship tournaments were even televised.

Here’s everything you need to know about the lost sport and those who championed it.

What is octopus wrestling?

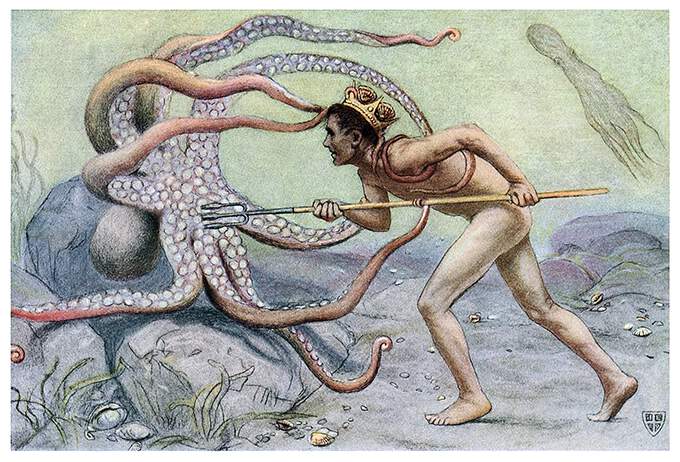

It’s exactly what it sounds like—teams of divers, some with equipment and some with just aqualungs, swam into water up to 60-feet deep in search of a Pacific giant octopus. Once they found one they’d “wrestle” it out of its cave and drag it to the surface. There were no chokeholds, half-nelsons, or any other traditional wrestling moves involved though. If anything the octopus would attach itself to the diver, who either swam or was reeled back to the shore by his teammates, at which point the detaching process began.

How did it get started?

It’s hard to say exactly how octopus wrestling got its start worldwide, but the earliest known account came in 1949 when Wilmon Menard wrote about a trip to Tahiti in which he helped a native hunter capture an octopus with giant tentacles. The article, “Octopus Wrestling Is My Hobby” went on to inspire people in Washington’s Puget Sound area to wrestle their own cephalopods, and the sport swelled in popularity for the next decade or so.

When was it popular?

Octopus wrestling reached the height of its run in the 1950s and the 1960s, when hundreds of people would congregate on the Puget Sound shores to watch teams of divers brave the chilly waters and extract unsuspecting octopuses from their dens.

Wait, why was this popular?

To understand the appeal at the time, you need to put yourself in the mindset of people living in the era. The Second World War had just ended, and the public’s appetite for monsters and sci-fi fiction was insatiable. Add in the fact that underwater diving was becoming a thing and the thought of everyday men heading into the ocean to wrestle a cephalopod was escapism at its finest.

How did you win?

The team that dragged the heaviest octopus back to the shore was crowned champion, while bonus points were given to teams that wore snorkels instead of diving equipment.

So… the animals pretty much lost.

In theory—it’s obviously never a fun day when someone comes into your home, detaches your tentacles and then drags you out. The octopuses that were caught during this particular fad of a sport were either released back into the wild, sent to the aquarium, or eaten. Very little about it was humane.

What’s this about it being televised?

At the height of octopus wrestling’s popularity in 1963, the world championship that year was televised. Of course underwater camera technology was only beginning to take flight, so those that tuned in basically saw a bunch of people wade into the water and then disappear for a long period of time. Not exactly titillating television, now is it?

Was it dangerous?

Pacific giant octopuses are fairly gentle creatures, but their tentacles can detach a breathing apparatus if a diver isn’t careful. Still, in the years that octopus wrestling was a thing no humans ever actually died from it. Sadly we can’t say the same for the animals involved.

Do people still do it today?

Interest in the sport died by the mid-1960s, but it wasn’t until 1976 when Washington State cast out a law that made it illegal to capture or harass an octopus. Wrestling for sport itself has been banned since 2010, but in 2012 diver Dylan Mayar trained and prepared to capture an octopus and drag it to shore. Since he planned on eating the animal it was technically legal (divers were still allowed to hunt one octopus daily for food), but people were not happy once Mayar’s gross stunt went public.

Meanwhile, now that we know octopuses have similar brain functions to humans, it seems unlikely that we’ll ever go back to that dark time again.