The skull of a mighty unicorn has just been discovered in Kazakhstan, which has forced scientists to rethink longheld theories about the survival of an extraordinary species, to look again at where it walked the Earth, and reassess how long it could have survived in some regions of the globe.

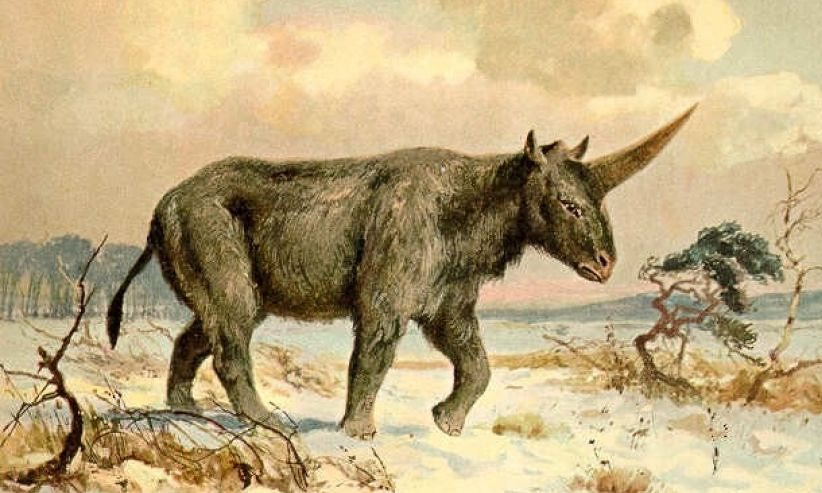

The mythical sounding beast in question is the Elasmotherium sibiricum, an animal that more closely resembled a great lumbering, shaggy-haired rhino than the Disneyfied version you may have prancing around in your head right now, but was a bona fide unicorn nonetheless. Thought to have stood 2m metres tall and 4.5m long, the four-tonne grass-munching monster boasted a huge single horn protruding from the middle of its forehead.

The skull, unearthed in the Pavlodar region of Kazakhstan by researchers from the Tomsk State University (TSU) and dated by the 14CHRONO Centre in Belfast using radiocarbon techniques, has revealed that the Siberian unicorn was still stalking parts of the planet 29,000 years ago. The result has surprised scientists, who previously believed it had become extinct some 320 millennia earlier. This new date means that people shared the planet with Siberian unicorns, with most paleoanthropologists agreeing that modern humans evolved in Africa about 200,000 years ago.

Scientists have long known that the Elasmotherium sibiricum once roamed across a range extending from Russia’s Don River to the east of modern Kazakhstan, but until now it was presumed to have died out about 350,000 years ago. The discovery of this excellently preserved skull, thought to belong to an elderly male, was first reported in the American Journal of Applied Science. It reveals that a branch of the species survived in one corner of the globe much longer than the majority of its kind, and scientists are now looking into the reasons why this might have happened.

‘Most likely, the south of Western Siberia was a refúgium, where this rhino persevered the longest in comparison with the rest of its range,’ Andrey Shpanski, a paleontologist at TSU, told Phys.org. ‘There is another possibility that it could migrate and dwell for a while in the more southern areas.’

The discovery could also reveal factors that are important to the potential survival of our own species. ‘Understanding of the past allows us to make more accurate predictions about natural processes in the near future,’ said Shpanski. ‘It also concerns climate change.’