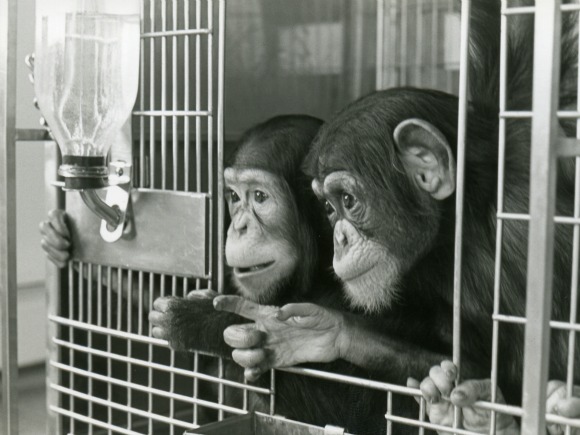

Chimps are incredibly like us humans—a connection that has cost the species big time. At one point there were thousands of chimps being used globally as human-replacements in research studies, though today most of these animals are long retired.

But according to the American group PETA, 900 or more chimps are still held in labs across the US—the country being the last holdout for great ape research in the world aside from Gabon. About 700 or so of these chimps belong to, or are sponsored by, the American National Institute of Health, but in the last few years the agency has been reconsidering their stance on ape-ownership. Last week in a decision that surprised animal research advocates, NIH announced it would be shutting down its chimp programme entirely.

The chimp-trade really began in the 1920s, when American experimenters began purchasing infant chimps captured from West and Central African forests. Though few chimps made it to maturity—suffering high mortality rates during their kidnapping, transport, from the stress of captivity and disease—this didn’t dissuade researchers.

In the 1950s the US Air force secured 65 young chimps for use in flight experiments in New Mexico, their offspring became crash-test dummies for seat belts and infectious disease guinea pigs. During the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis the NIH was breeding chimps with such intensity that in 1995 the surplus of animals sparked a breeding moratorium—plus chimps didn’t prove to be a good human model for the disease.

When the European Union finally banned great-ape experimentation in 2010, there was already a debate in the US as to what to do with captive research apes, NIH’s chimps in particular. After it was shown that the animals weren’t a necessity, and the 2013 amendment of the CHIMP act, 310 of the NIH fleet were retired, 50 animals kept on as an emergency reserve.

The retirement process has proven tricky, both in terms of cost and lack of resources. There’s currently only one federal sanctuary in the US, Louisiana’s Chimp Haven, which is quickly reaching capacity. But last week NIH director Francis Collins declared in an email that the reserve group would also be sent to sanctuaries.

Collins wrote that 20 chimps will be moved from Texas’s Southwest National Primate Research Center to Chimp Haven, and then 139 animals transferred from University of Texas’s Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research to a destination yet to be determined. After that, the agency will have to figure out how to handle the 82 chimps still under their care at the National Primate Research Center.

Though it’s been a long time coming, the NIH’s announcement very likely marks the beginning of the end—a final point before the closure of a painful and controversial chapter of chimp-human relations. To help along the matter, the US Fish and Wildlife Service granted captive chimps’ endangered-species protection this past June—meaning studies using the animals must somehow benefit chimps in the wild. Collins says since 2013 there’s only been one, unsuccessful application requesting use of their animals. US FWS says they’ve had none.