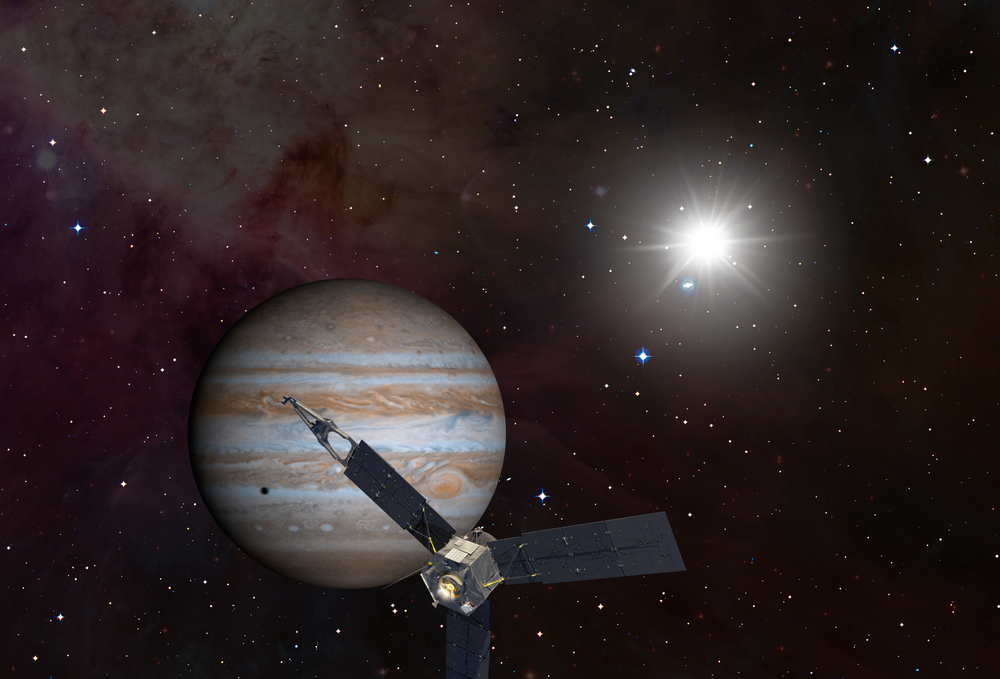

At six minutes to midnight on the fourth of July (Eastern Standard Time), the collected cast and crew at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, went totally wild. The exploratory probe Juno had just successfully gone into orbit around Jupiter, having navigated into one of the most hostile environments in our solar system—and it was still working.

Juno blasted off from Earth on 5 August 2011 and has been hurtling towards the gas giant Jupiter ever since, but its entire mission depended on the final 35-minutes of its five year flight. When it came within 2,609 miles of the planet, a British-built engine needed to fire up and slow the solar-powered probe down sufficiently for it to be caught by Jupiter’s gravitational pull. If the engines failed to fire at precisely the right time, the probe would overshoot the planet and continue out into the ether of deep space. It takes almost 49 minutes for signals from Jupiter to reach Earth, so if anything went wrong there was no possibility of a remote fix.

The engine fired faultlessly at 11.18pm EST, but then the little probe had to squeeze through a narrow band and skim the surface of Jupiter to avoid the worst of its brutal radiation belt (so savage that the crucial workings of the little craft had to be been encased in a titanium vault) and its dangerous dust rings.

The nervous wait for everyone involved in the project, and all interested onlookers from Planet Earth, came to an end with a handful of words: ‘All stations on Juno co-ord, we have the tone for burn cut-off on Delta B,’ Juno Mission Control announced. ‘Roger Juno, welcome to Jupiter.’

Amid scenes of whooping and backslapping, the team tore up their contingency communication strategy and Scott Bolton, principle investigator of the Juno mission, told his people: ‘You’re the best team ever! We just did the hardest thing Nasa has ever done.’

And now the real work begins. Scientists will use Juno to explore the deep interior of the enormous and enigmatic four-and-a-half-billion-year-old planet, peeling back the layers of gas that form this eye-wateringly immense onion to see what really lies within. Among the disputes scientists hope to resolve is the hotly debated question about whether Jupiter does have a solid core.

Bolton said he personally wanted to understand more about Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a giant storm, big enough to swallow Earth three time over, which has been raging for centuries.

‘I love that Great Red Spot,’ he told reporters. ‘We see it evolving, and it’s been getting smaller ever since I first got amazed by it, which was when I was a child… The fact that it’s lasted so long—there are records of it going back hundreds of years—means that it must have fairly deep roots.’

The mission goal, as stated on NASA’s website, is to: ‘Understand the origin and evolution of Jupiter, look for a solid planetary core, map magnetic field, measure water and ammonia in deep atmosphere, observe auroras.’

In order to do this, the spacecraft will circle Jupiter once every 53 days, until October 14, when it will change to a tighter 14-day orbit. It’s believed that at least one of Jupiter’s 63 moons, Europa, could harbour life, so to avoid any possibility of contamination, Juno will be deliberately plunged into the destructive heart of the planet when its mission is complete, in around 20 months time.

The moon closest to Jupiter is volcanic Io, with the next one out being the ice-crusted ocean world Europa, followed by gigantic Ganymede and cratered Callisto. When Galileo first observed these moons and realised they were in orbit around Jupiter, it forever changed humankind’s appreciation of our position in the cosmos, which was previously thought to revolve around us.

[geoip-content not_country=”CA”]

If you’d like to learn more about the incredible mysteries of our solar system, why not check out our selection of stellar space documentaries—now streaming on demand on Love Nature. To watch, simply sign up for your 30-day free trial today.

[/geoip-content]