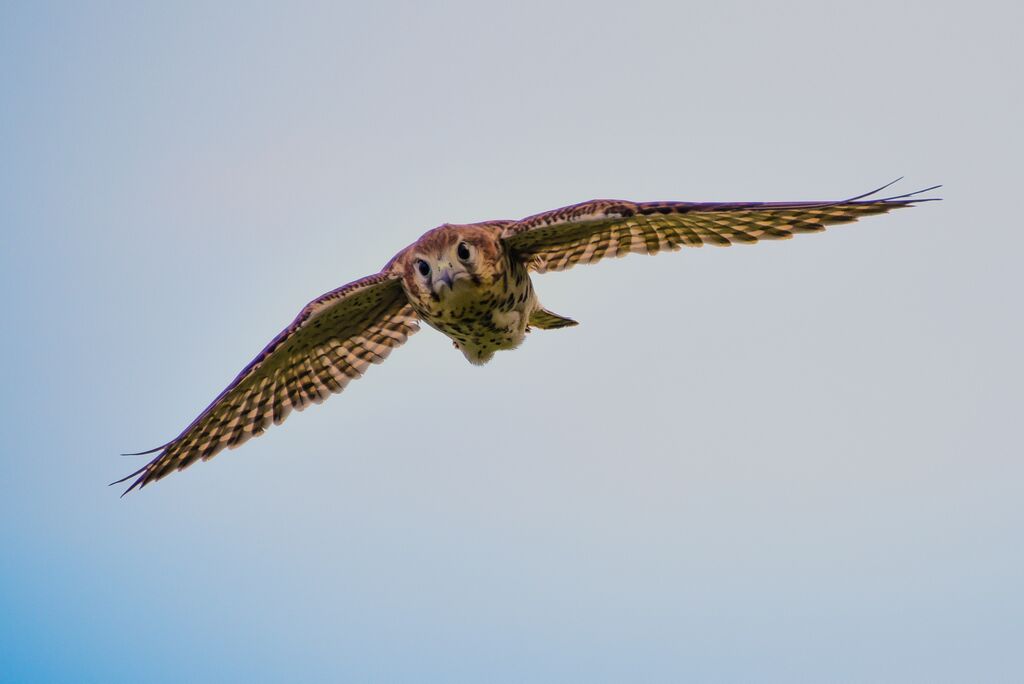

In the land of the dodo, endangered endemic species such as the Mauritian kestrel are pulling out of a dramatic death dive to star in an extraordinary story of last-gasp survival.

Wander into any gift shop on Mauritius, a verdant green droplet on the vast blue canvas of the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar, and you’ll find ample evidence of the bird that made this far-flung scrap of land famous. There are dodos everywhere. Fluffy toy dodos, paperweight dodos and dodos that perch on pencils.

It’s been absent from the island—and the planet—for 350 years, but there’s an enduring fascination with this hapless bird, which was pushed over the edge of existence by humankind within a few short years of its island home being discovered, and has since achieved a form of unfortunate immortality by becoming the universally recognised icon of species extinction.

Seventeenth century, Dutch sailors, at sea for months en route to India and the Spice Islands and famished for anything that wasn’t rancid salty meat and weevil-infested biscuits, fell upon the island in a furious feeding frenzy. By then the dodo—a meaty, flightless, slow-moving bird with no natural predators—had evolved into the perfect dinner. When they departed, the Dutch left behind nest-raiding rats and other egg-eating animals (dogs, pigs, cats and macaques), which finished the job. By 1662 the species was extinct. Dead. Gone, but not forgotten.

The dodo may haunt Mauritius, but beyond the ghost stories the island has another tale to tell—a remarkable one about the fight for species survival, which I’ve come to hear firsthand from members of the organisation that spearheaded it: the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation (MWF).

‘With just four individuals left alive in the world in 1974, the Mauritian kestrel was recognised as the most endangered bird on Earth’

In early 1970s, the Mauritius kestrel looked to be going the way of its ill-fated feathered compatriot. This magnificent bird of prey—endemic to the island, just like the dodo—was hovering on the precipice of extinction, with a wild population you could count on the fingers of one hand, without having to use your thumb.

It wasn’t hungry sailors that threatened the kestrel, but environmental pressures. Some were long-standing, including the steady deforestation of the once uninhabited island as the human population grew throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Feral canines, cats, rats, mongoose and monkeys didn’t help, but the most dramatic decline was caused by the arrival of a different species of visitor: the modern tourist.

By the 1960s Mauritius had ambitions of becoming a holiday hotspot, but if there’s one thing that’s going to ruin a destination’s reputation for carefree recreation, it’s malaria. Locals weren’t overly enamoured with the tropical disease either, and throughout the 1950s and 60s, the island was liberally sprayed with DDT to destroy mosquitoes. Unfortunately, it wasn’t just the insects that were killed.

‘The DDT made the kestrel’s eggs infertile,’ explains Dr Nicolas Zuel, the MWF’s Fauna manager. ‘It also reduced the thickness of the egg shells, making them brittle and easily broken.’

With just four individuals left alive in the world in 1974, the Mauritian kestrel was recognised as the most endangered bird on Earth. The one small fleck of fortune in this otherwise dire scenario was that two of the surviving birds were a breeding pair.

A desperate rescue bid was launched by an international collective of conservationists, including Gerald Durrell. A precursor to the MWF launched a dedicated program to save the species in 1974. Cornell University’s Stanley Temple, assisted by Jersey Zoo in Britain (now Durrell Wildlife Park), tried breeding the kestrels in captivity, but the attempts ended in disappointment.

A more radical approach was required to pull the kestrel out of its death dive, and this was provided by a British biologist who came to the island in the employ of Birdlife International in 1979. Carl Jones had bred kestrels in his backyard as a child growing up in Wales and had an in-depth knowledge and a passion for falcons. Taking over the project—by then widely believed to be doomed—he introduced new methodology.

‘From being critically endangered in 1979, the species gently ascended the list to become ‘endangered’ in the mid 1990s and merely ‘vulnerable’ by the millennium’

He climbed trees to collect eggs from the nest of the breeding pair, and supplemented the parent birds’ diet so they could reproduce quicker. The liberated eggs were hatched in a sanctuary on Ile aux Aigrettes, a tiny islet off the east coast of Mauritius.

Jones, who eventually left Birdlife to co-found the MWF with Durrell, used innovative breeding techniques such as cross-fostering and double-clutching on the island, to further increase the fertility of breeding pairs, and pioneered hacking techniques—teaching hand-reared kestrels how to catch prey.

Within 12 months, over 300 kestrels had been raised and returned to the wild. From being critically endangered in 1979, the species gently ascended the list to become ‘endangered’ in the mid 1990s and merely ‘vulnerable’ by the millennium. In 1996 the MWF broadened its scope (to take on habitat restoration and land management) and adopted its current name, with the Mauritius kestrel as its emblem.

Dr Nicolas Zuel tells me there are currently 350–400 kestrels on the island. Incredibly, despite how far into the shallows of the gene pool the species waded, no significant issues have been recorded. ‘There was inbreeding,’ he says. ‘But we didn’t notice any problems.’

Ile aux Aigrettes remains a wildlife sanctuary operated by the MWF, but Lissette, the guide showing me around, says there are currently no kestrels on the island. What there are, though, are plenty of pink pigeons—another bird unique to Mauritius that was brought back from death’s door by the efforts and expertise of Jones and the MWF.

The list of endangered endemic species that the organisation is now working with on the island include the Mauritius fody, the echo parakeet and the Mauritius fruit bat, which owe their existence to techniques and methods developed during the fight to save the Mauritius kestrel.

‘As long as work is done for the conservation of the birds…they have a positive future. But if nothing is done, the birds face the risk of disappearing’

In Frédérica Nature Reserve on the forested fringe of Black River Gorges National Park, I finally come closer to the kestrel itself. Here, in the woods where Jones first focused his expert eye on the near-extinct species in 1979, breeding boxes designed for the kestrels can be seen in the trees and mongoose traps lie in the undergrowth. Many kestrels were reintroduced to the wild here, and their numbers are healthy, but they remain stubbornly elusive. In seven years working here, my guide Vishal has seen just 10.

At a MWF field station, two female rangers diligently check the boxes and make notes. The program is still active, but the methods used and the level of interference with the birds varies according to the size of the population at any given time.

‘Right now we were just monitoring the birds,’ Dr Zuel tells me. ‘But as the population is decreasing we will restart captive breeding. Pairs are kept in captivity and their young are released in appropriate habitat.’

Even now, with numbers almost as high as pre-colonial times and their worst threats being monitored, Dr Zuel cautions against complacency and stresses how fragile the species remains. ‘As long as work is done for the conservation of the birds and protection of their habitat, they have a positive future,’ he says. ‘But if nothing is done, the birds face the risk of disappearing.’

Flying out of Mauritius, as the plane roars over Ile aux Aigrettes, disturbing the reverie of its population of pretty pink pigeons, I grab a notepad to make notes about this staggering survival story. The only writing implement I can find is a pencil I bought for my daughter at the MWF shop on the island. It has a wobbly dodo on top. How appropriate. Because it’s the backstory that puts all this in perspective—a tragic tale of permanent loss that brutally underlines the need to protect species for future generations.